|

| American Robin (Turdus migratorius) |

Robin in the rain

Such a saucy fellow.

Robin in the rain

Mind your socks of yellow.

Running in the garden on your nimble feet,

Digging for your dinner with your long strong beak.

Robin in the rain,

You don't mind the weather

Showers always make you gay.

Bet the worms are wishing you would stay at home,

Robin on a rainy day – don't get your feet wet,

Robin on a rainy day!

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last Saturday, 9/30/2017, I arrived at the nursery at 7 AM but I didn't report to anyone because no one was scheduled to work that weekend. Finally, two days to myself without employees or customers or delivery trucks...or problems, or complaints or broken equipment that would need repaired. Just me in a warm September drizzle. Our past summer was long and brutal with the irrigation team keeping the nursery vital almost every day of the week. Often I would have business to attend to in a certain greenhouse, but after a five-minute walk to the location I would discover the greenhouse engulfed with irrigation, and I would have to mentally reschedule my visit. Imagine the annoyance of trying to cut 25,000 maple scions – from 400 different cultivars – while dodging the damn sprinklers!

But today we're overcast and in the mid-60's for the high temperature. The earth exudes its petrichor*, the earthy scent produced when rain falls on dry soil. Today it is baking and muggy in Baghdad and Calcutta but we are crisp and clean in western Oregon, and there is the temptation to shed my clothes and prance naked amongst the trees. Oooh– sorry for the visuals.

*“Petrichor” is from Greek petra meaning “stone” and ichor, referring to the fluid that flows in the veins of the gods in Greek mythology.

| GH18 |

| Acer palmatum 'Summer Gold' |

I stick to the greenhouses to avoid the rain and my first stop is GH18 where we keep the maple grafts. I have visited at least once a day since July 17th, our first day of grafting, and I like to flick off the half-inch petioles which after three weeks is an indication that the graft has taken. These will eventually fall off by themselves, especially when new growth appears at the fourth or fifth week on the scion, but I like to initiate the process. A year ago we achieved an excellent grafting percentage, but every season is different and I worry about the prospects for every one of the 25,000 that we did this summer. At least the Acer palmatum 'Summer Gold' grafts look good at this point.

|

| Acer macrophyllum 'Mocha Rose' |

|

| Acer macrophyllum 'Golden Riddle' |

|

| Acer macrophyllum 'Santiam Snow' |

The Acer macrophyllum cultivars are looking good as well. Not many companies produce forms of the “Big-leaf maple” because they're only hardy to -10 degrees (USDA zone 6) and because of their eventual size. A hundred grafts per year is enough for me, and this summer we divided the rootstock up for 'Mocha Rose', 'Golden Riddle' and 'Santiam Snow'. The intention will be to list them for sale at 4-5 years of age when they'll be about 8'-12' tall. I planted all three cultivars in full sun in the Quercus section at Flora Farm and eventually the canopies will mingle. I was especially pleased that the variegated 'Santiam Snow' held up without significant burning on our 106 degree day in July. The newly planted 'Golden Riddle' did burn – not surprising for an unestablished golden tree – but then new growth appeared in August and it withstood a number of 90 degree days. I guess that I mess around with these macrophyllums because the species is native to Oregon's woods and I have known the big monsters all of my life. It was introduced to Europe by Scotsman David Douglas in 1826 and scientifically described by the German-American botanist Frederick Pursh who was noted for studying the plants collected on the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Davidia involucrata 'White Dust'

Davidia involucrata 'Aya nishiki'

|

| Davidia involucrata 'Lady Sunshine' |

Last year we grafted Davidia involucrata cultivars at the same time (August) as the maples with great success, so we're hoping for the same results again this year. We did a small number of 'White Dust' which we propagate about every third year...just to keep a few trees around the nursery. I don't really care for its white variegation but I am impressed with the reddish new growth. 'Aya nishiki' can be spectacular – like in Tokyo where the summers are humid – but Oregon's dry 106 degrees scorched the variegated leaves. Still, it's good to keep a few trees around. The bulk of our rootstocks are reserved for 'Lady Sunshine', a cultivar that is as spectacular as any variegated tree. It was discovered and introduced by Crispin Silva of Oregon, a plantsman with a small nursery, but notable for a large number of worthy plant introductions.

Stewartia monadelpha 'Pendula'

Last year we grafted about fifty Stewartia monadelpha 'Pendula' onto Stewartia pseudocamellia rootstocks. It was a 100% failure as zero grafts took. Hmm...was it because the crew spaced out and forgot to vent the poly on a very hot day? It was probably 150 degrees under the poly and the rootstock leaves burned, or did the grafts not take due to another reason or reasons? Stewartias are notoriously difficult to graft anyway, and one hates to scar the expensive rootstocks. With S. monadelpha as rootstock I achieved 15% success for 'Pendula' one winter with grafts placed on the hot pipe, and that has been my best result yet. I'm still growing these expensive trees on to a larger size before selling, and I will need a couple hundred dollars each before I can break even. I am unaware of anyone else in America who is producing this cultivar, with my start coming from Japan. I think it is a recent horticultural discovery, so the 'Pendula' name is not valid, and I would love to know what it is really called in Japan.

| Cornus florida 'Autumn Gold' |

Ok, that's enough time with new grafts in GH18 and I decided to wander into other greenhouses with more established plants. The end of September is an ugly time at the nursery with very little looking fresh, and not much yet in fall color. One exception was some containers of Cornus florida 'Autumn Gold', which normally turn a light golden color as the name implies. But as you can see (above) this year I am treated to some pink and purple leaves as well. 'Autumn Gold' flowers precociously, that is the cream-white blossoms (bracts) appear before the leaves, and then in fall the small red fruits blend spectacularly with golden foliage and golden-colored twigs. This wonderful dogwood is a selection from Don Shadow of Tennessee. We propagate by grafting onto Cornus kousa rootstock in winter on our hot-callus pipe.

| Rhododendron luteum |

In the same greenhouse I discovered that the deciduous Rhododendron luteum was displaying rich red autumn leaves, while a few old yellow flowers from summer were still clinging to the bush. R. luteum is known as the “yellow azalea” or “honeysuckle azalea,” and is a species native to southeastern Europe and southwestern Asia. The blossoms are strongly perfumed, too much really, and one year when I brought a bouquet into the house my wife threw it out in less than an hour. Besides, the nectar is toxic, and the Greeks knew as early as the 4th century B.C. the dangers of R. luteum bee honey when supposedly 10,000 soldiers in the army of Xenophon became ill along the Black Sea coast of Turkey. R. luteum should not be confused with R. lutescens, the latter being evergreen and coming from southwest China.

Calocedrus decurrens 'Berrima Gold' at Arboretum Trompenburg

GH12 is a graft house where we heat it up in winter and produce various evergreen conifers. We've never had such a good take before on Calocedrus decurrens 'Berrima Gold' as last year and I think every one of the 500 grafts was successful. Due to last winter's abundance I decided to not purchase rootstock this year as 500 of any one conifer is quite a few for our small company. 'Berrima Gold' is especially attractive in the winter garden with its orange twigs and glowing golden foliage, and a mature specimen is particularly useful in the landscape due to its narrow habit. The largest tree that I have ever seen is growing at Arboretum Trompenburg in Rotterdam, just in front of the late Dick van Hoey Smith's house. The genus name is from Greek kalos for “beautiful” and cedrus for a “cedar tree,” and Calocedrus is a member of the Cupressaceae family.

|

| Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 'Wissel's Saguaro' |

GH12 also contains a nice crop of Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 'Wissel's Saguaro' from last winter's grafting. All of them are borrowing the disease resistant lawson rootstock 'D.R.', and shame on any company that peddles a lawson cultivar on its own roots. Today's GH12 tour indicates that Buchholz Nursery will be well-stocked in the future with C. lawsoniana grafts as well as numerous Chamaecyparis obtusa cultivars grafted onto Thuja occidentalis 'Smaragd'. We sell these trees as 1-year grafts all the way up to 25-year-old specimens – in other words there will be Buchholz trees for sale long after I am gone.

| Acer ex rufinerve 'Winter Gold' |

Acer x conspicuum 'Phoenix'

A few years ago I purchased 50 trees of Acer ex rufinerve 'Winter Gold' and now they are 7-8' tall at the northeast corner of GH15. How fast they grew! When I placed my order I wasn't paying attention and I thought I was buying 'Winter Gold' itself. The “ex” before the name is a ploy that reveals you are buying seedlings with 'Winter Gold' as the mother tree. In any case they all look alike – you could say that they “came true” – and all are glowing with yellow-orange stems. I'll plant a couple out in the gardens and try to sell the remainder. Hopefully they'll be stronger than the one last Acer rufinerve 'Erythrocladum' that was 90% dead in the garden last winter, and that we finally tossed onto the burn pile. I wasn't sorry to see it go because horticulture doesn't need a rufinerve 'Erythrocladum' since we already have a pensylvanicum 'Erythrocladum'. Both cultivars are wimps, of “weak constitution” as Hillier puts it in his Manual of Trees and Shrubs. For winter-red bark we favor Acer x conspicuum 'Phoenix'. The xconspicuum hybrid is Acer davidii x Acer pensylvanicum, with 'Phoenix' originating as a seedling of A. x. c. 'Silver Vein'.

Polystichum setiferum 'Bevis'

We are growing a frothy fern in GH23, Polystichum setiferum 'Bevis', and it is commonly called the “Bevis European soft shield fern.” This week I hope for a dry day and I'll put it in the garden where it belongs, as I only have the one and it's in a crowded greenhouse. As usual with ferns I turn to Sue Olsen's Encyclopedia of Garden Ferns, and she calls the “Bevis Group” “the cherished treasure among P. setiferum cultivars.” Sue relates that it was named for Mr. Bevis who was in charge of trimming hedge banks in Devon, England. He discovered it in 1876 and had the skill and presence of mind to recognize it as different. “It has been a great gift to horticulture ever since.” I have a perfect place for mine in the Display Garden in the shade of an Acer palmatum 'Sherwood Flame'.

| Fagus sylvatica 'Bicolor Sartini' |

|

| Fagus sylvatica 'Albovariegata' |

In the same house as the Bevis fern is Fagus sylvatica 'Bicolor Sartini', a cultivar with pale green leaves edged with yellow variegation. I grow one in full sun at Flora Farm, and although it doesn't burn it is largely a non-event in the Oregon heat. I imagine it is best in partial shade – but not too much! – especially with a backdrop of dark green evergreens. We also house Fagus sylvatica 'Albovariegata', but I insist the crew keeps them separate and far apart from 'Bicolor Sartini'. A word of cultural advice is to prune both cultivars into bushy shrubs, for the color is more apparent when looked at rather than up at.

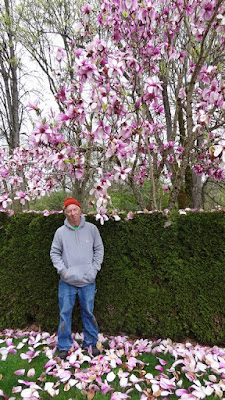

Magnolia x 'March Till Frost'

What's that...at the end of the greenhouse? Ah, a Magnolia in bloom, and it turns out that it's the cultivar 'March Till Frost'. It's a complicated hybrid of (Magnolia liliiflora x M. cylindrica) x M. x'Ruby'. It was accomplished by August Kehr in 1997 and it really does bloom as the name implies. Another specimen now in flower is planted along the long road to my home, and I like to surprise my wife with these floral treats as she ferries the kids to school and runs a million other errands. 'March Till Frost' will not grow to a huge size, but I imagine it will get to at least 20' tall, judging by what I have seen so far.

| Quercus alnifolia |

I have one Quercus alnifolia at the nursery, gifted to me by Guy Meacham of PlantMad Nursery, a company known for “Growing Plants for the Fun of It!” I'm not positive but I think he produces the curious “Golden oak of Cyprus” from rooted cuttings. Its common name is due to its dark, glossy rounded leaves which are colored yellow beneath, and I never fail to lift up a leaf for visitors. Q. alnifolia can be found in the Troodos Mountains of Cyprus so I don't know how hardy it is. Although Cypress[sic] is the third largest island in the Mediterranean, I suspect that 99% of USA high school graduates could never locate it on a world map. I'm not bragging because I can, but I mention it because the geography of plant origins has been my life-long hobby and some of the highlights of my life have been to visit them in the wild.

I have one Quercus alnifolia at the nursery, gifted to me by Guy Meacham of PlantMad Nursery, a company known for “Growing Plants for the Fun of It!” I'm not positive but I think he produces the curious “Golden oak of Cyprus” from rooted cuttings. Its common name is due to its dark, glossy rounded leaves which are colored yellow beneath, and I never fail to lift up a leaf for visitors. Q. alnifolia can be found in the Troodos Mountains of Cyprus so I don't know how hardy it is. Although Cypress[sic] is the third largest island in the Mediterranean, I suspect that 99% of USA high school graduates could never locate it on a world map. I'm not bragging because I can, but I mention it because the geography of plant origins has been my life-long hobby and some of the highlights of my life have been to visit them in the wild.| Acer mandshuricum |

I thought I was done talking about maples, but I noticed that just out of the western door of GH23 we have a half dozen Acer mandshuricum. I couldn't miss them because they are currently adorned with royal purple-red foliage. The species is one of the first to color in autumn, but then it's also one of the first to leaf out in the spring. I have described the species sufficiently before, and I only mention it now because the leaves went from green to purple so suddenly. Also, a western shaft of sunlight has just pierced the overcast sky and is now shining upon them. I don't know why the species is spelled mandshuricumwhen it is commonly called the “Manchurian maple.” Anyway it is a wide-spread species that comes from much of eastern China...up to Korea and Russia. It is rarely seen in Western gardens because it leafs out so early and can be damaged by spring frosts. However, a nice specimen is growing at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston that is over 70 years old and is over 40' tall. It was still green early last October when I saw it – for some reason – because when I returned home my tree was in full autumn color.

Acer palmatum 'Purple Curl'

One last maple to describe is Acer palmatum 'Purple Curl', and the original tree is in GH15 with some other seedling selections. It's different, although I'm not really sure how much I like it. Also, I wonder if it contains any Acer shirasawanum blood in it, even though the seed mother was Acer palmatum 'Purple Ghost'. Yikes – old Buchholz sets aside large quantities of seedling selections, so expectedly quite a number of them don't really pan out. Will I drop 'Purple Curl' altogether or will I eventually produce thousands of them? As they say: “we'll see, time will tell...”

|

| Calico Critters |

My solo Saturday tour was...interesting but not great. I made mental notes about next week's work projects as is my wont. I reported that I had a “good day” when asked by my wife, but then any day alone is usually pretty good for me. When my daughter S. was 8 years old she descended to the basement alone to play with her toys. After an hour I went down to see her and I asked if she was ok or if she was unhappy to be alone. She responded, “I wasn't alone – I was with my Calico Critters so I'm pretty happy.”